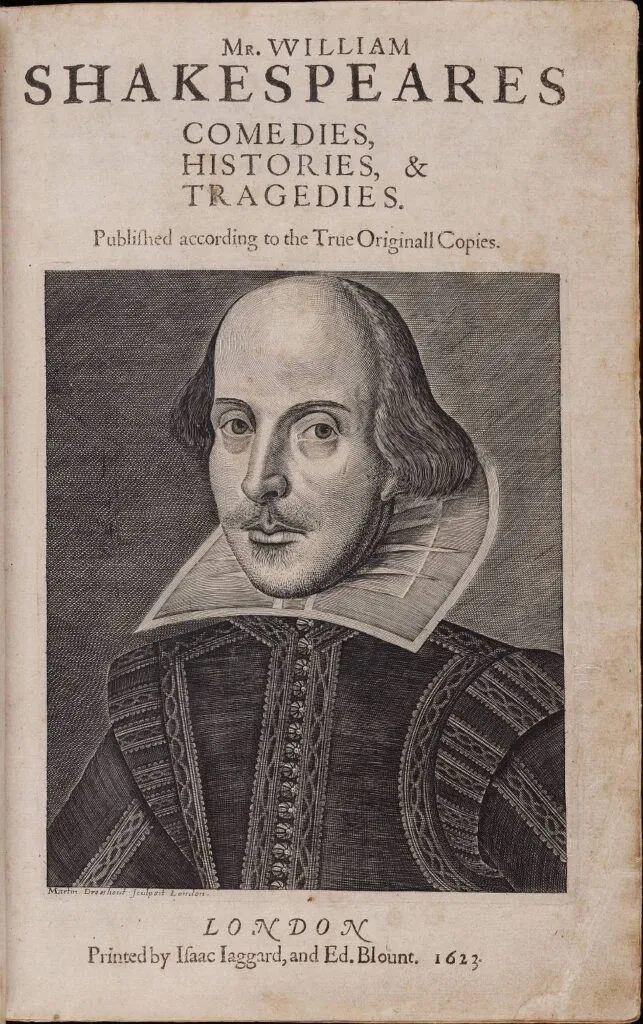

(Angelo Paratico) Not all historians believe that a semi-illiterate impresario like William Shakespeare could have written all the masterpieces attributed to him, which are steeped in Classical and Renaissance culture. One of the most widely accepted theories identifies the true author as Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (12 April 1550 – 24 June 1604), often referred to simply as ‘Oxford’. Queen Elizabeth was always very close to De Vere, a man of great literary talent, through all her ups and downs. Elizabeth forgave Oxford many things, including making pregnant one of her ladies-in-waiting, and granted him a pension after he had squandered a fortune on his excesses and fallen into debt. It was said that the saying: inglese italianato, diavolo incarnato goes back to him. Historians who regard Oxford as the true author of Shakespeare’s plays argue that circumstantial evidence favours his role and suggest that the seemingly contradictory historical evidence is part of a cover-up to protect the identity of the true author. The Oxfordians’ arguments rely on biographical allusions that correspond to events and circumstances in Oxford’s life. The argument also relies on perceived parallels in language, idiom and thought between Shakespeare’s works and Oxford’s own poems and letters. The fact that no plays under Oxford’s name have survived is also important to the Oxfordian theory. According to this scenario, Shakespeare was merely a ‘front man’ or ‘theatrical facilitator’.

Edward de Vere, Oxford, left England in the first week of February 1575 and was introduced to the King and Queen of France a month later. In mid-March he travelled to Strasbourg and then on to Venice, where he settled en route to Milan. He stayed in Italy for a year, during which time he was clearly fascinated by Italian fashion in clothing and literature. According to John Stow, he introduced certain Italian luxuries to the English court which immediately became fashionable, such as perfumed, embroidered or decorated gloves worn by Elizabeth, which were known for many years as the ‘Earl of Oxford’s perfume’.

In January 1576 Oxford was in Siena and left Venice with a stopover in Verona in March with the intention of returning home via Lyon and Paris, although a later account places him further south, in Palermo.

This would explain why most of Shakespeare’s plays are set in Italy. In fact, only ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’ is set in England. Take Verona, for example, where Oxford must have spent a lot of time, as the city features in ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and ‘The Two Gentlemen of Verona’.

On his return, Oxford learnt that his wife Anne had cheated on him and refused to live with her, even though she was the daughter of the powerful William Cecil, who had been the shadow of Elizabeth I for forty years. He took up residence at Charing Cross and, at the Queen’s request, allowed his wife to visit her at court, but only when he was not present, and insisted that she never attempted to speak to him again.

The most convincing evidence put forward by opponents of the Oxford theory is the fact that Oxford died in 1604 and Elizabeth I in 1603. However, since the generally accepted chronology of Shakespeare’s works places the composition of some twelve works after these dates, they argue that it would not be credible to attribute them to an earlier period. However, Oxfordians counter that the annual publication of ‘new’ or ‘corrected’ Shakespeare works ceased in 1604 and that the dedication of Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnets’ indicates that the author had died before their publication in 1609. Proponents of the Oxford hypothesis believe that the reason why many of these ‘late works’ show traces of heavy revision is precisely because they were completed by other playwrights after the deaths of Oxford and Elizabeth. Well, these revisions are largely attributable to an Italian, John Florio (1553-1625), and on this point even the anti-Oxfordians agree.

John Florio’s father, Michelangelo, was born in Florence in the first decade of the 16th century into a Jewish family that had converted to Catholicism. He entered a Franciscan monastery and became a monk, but then changed his mind and became a Calvinist, visiting and preaching in Faenza, Padua, Rome, Verona, Venice and Naples. At the beginning of 1548, he was imprisoned by the Holy Inquisition in Rome, in Tor di Nona. He managed to escape on 4 May 1550 and found refuge in Venice before travelling to England, where he met William Cecil, Oxford’s future father-in-law. He had a son with an Englishwoman, John, who was born in 1553. With the restoration of Catholicism under Mary I, the Florio family fled to Antwerp and Strasbourg. Michelangelo became a preacher in Bergell in Switzerland, where he remained until his death in 1567, while maintaining his contacts with England. In 1563, he translated a book by Agricola on metals into Italian and dedicated it to Queen Elizabeth I.

During 1570 the young Florio returned to England and began to make a name for himself as a scholar and translator. He wrote some truly original language manuals, First Fruits (1578) and Second Fruits (1591), and published the 1590 edition of Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia. His career peaked with his monumental translations of Montaigne’s Essays in 1603, Boccaccio’s Decameron in 1620 and the Italian-English dictionaries World of Wordes (1598) and Queen Ann New World of Words (1611). He was a friend of Giordano Bruno while working as a tutor and spy for Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham at the French ambassador’s house.

His greatest work, still in print in Britain, is his admirable translation of Michael de Montaigne’s Essays.

John Florio died in poverty in Fulham, London, in the autumn of 1625 because his royal pension had not been paid. His house in Shoe Lane was sold to pay off his large debts, but his daughter married well and Florio’s descendants became important figures.

Angelo Paratico