(Angelo Paratico) Fitzcarraldo is a 1982 film written and directed by Werner Herzog. The story is partly inspired by the life of the Peruvian Carlos Fitzcarrald (1862–1897), who, like the protagonist of the film, had a ship hoisted to the top of a mountain. However, Herzog was almost certainly unaware of what the Venetians accomplished in 1439; otherwise, he might have filmed between Verona and Rovereto, not in the Amazon.

An entire fleet was transported from Venice to Lake Garda to break the Milanese siege of Brescia and secure the Serenissima’s control of the entire lake. Venice was one of the oldest republics in Europe, otherwise dominated by hereditary monarchies. In the 15th century, Venetian policy, which had always focused on the sea, shifted towards the mainland: Padua and Verona were conquered, and Brescia voluntarily surrendered to the Republic of Venice.

For this reason, the Venetian Senate proclaimed Brescia “Lioness and worthy bride of the Lion,” conferring upon it the title of Brixia fidelis Fidei et Iustitiae. But the Visconti declared war on Venice to punish it for this betrayal. In 1438, the Duke of Milan marched on Brescia for the same reason.

The commander of the Milanese was Piccinino (Niccolò di Callisciana), a bitter enemy of Gattamelata, who commanded the Venetians. The Milanese troops occupied Peschiera and Desenzano to isolate Brescia from other Venetian territories and prevent it from receiving reinforcements across Lake Garda.

Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) managed to retreat from Brescia. After crossing the Peneda Pass and the Sant’Andrea Valley, he crossed the Val d’Adige near Mori, and the Venetian troops reached Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella, then San Pietro Incariano and Parona. They entered Verona between the evening of 28 September 1438 and the following morning. In Verona, they discussed their future strategy with the Venetian legates, Federico Contarini and Marco Foscari, who decided to carry out raids in the Mantua area and, above all, to recapture the bridge at Valeggio sul Mincio, where the road from Verona to Mantua passed.

Gattamelata left Verona on 12 January 1439, but Piccinino and Gonzaga immediately invaded the city. The Great Council of the Serenissima managed to approve a plan that seemed mad. It was 1 December 1438, and the proponents were Biasio de Arboribus and an expert Greek sailor, Niccolò Sorbolo. Gattamelata assured them of the necessary armed protection along the Adige River.

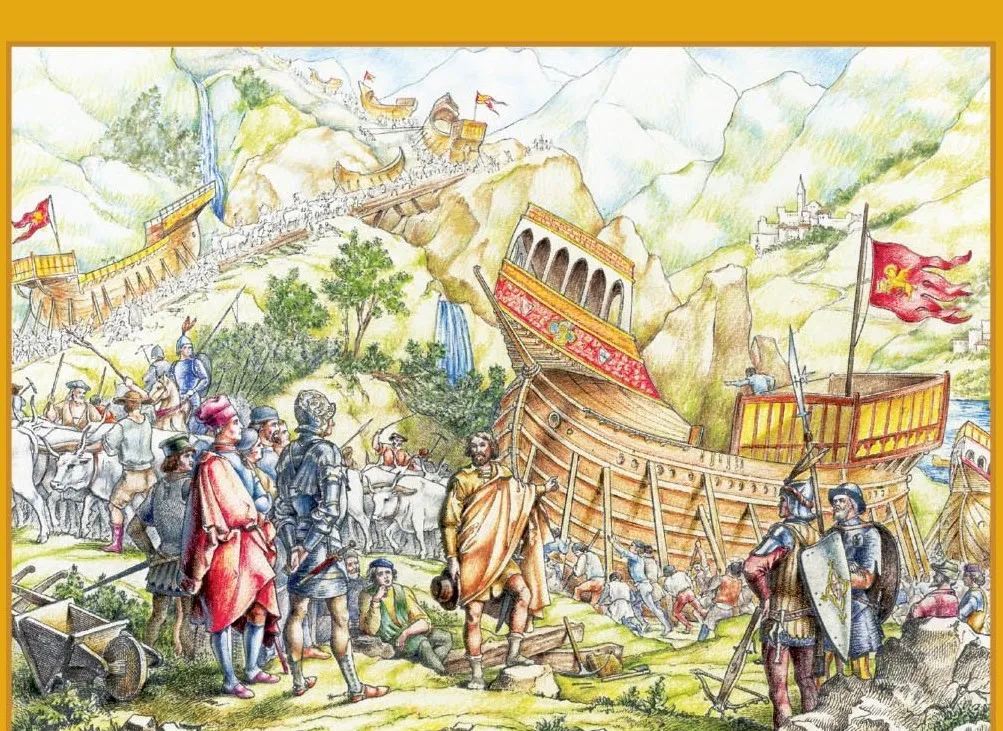

To break the siege of Brescia, the Venetians planned to bring an entire fleet to Lake Garda, passing through Verona and then the lands of Rovereto and Torbole. The Arsenale – the largest shipyard in the world – set to work, and in early 1439, a fleet of 25 large ships, plus two heavily armed galleys and six frigates, set sail and travelled up the Adige River. Venetian galleys usually had two masts, a main mast and a mizzen mast, but some had only one. The main mast could reach a height of 21 metres and supported a yardarm twice as long – almost as long as the entire hull – where a triangular sail, called a lateen sail, was attached. The fleet set sail from Venice and entered the mouth of the Adige near Sottomarina di Chioggia, sailing up the river to Verona. In the city’s river port, side floats were attached to reduce the draft and allow the journey to continue, as the river was low. The journey continued smoothly through the Ceraino lock to the village of Marco, just south of Rovereto.

At this point, the fleet was pulled ashore and transported from the Adige to Lake Garda. Almost six centuries later, their feat still arouses wonder. The ships were dragged towards Torbole using logs arranged on rails and covered with grease, with hundreds of oxen and men pulling them up and then down, making masterful use of the sails to slow their descent and assist their ascent.

The Milanese were certainly not idle. Their new initiative in the Verona plain, between the end of April and May, overwhelmed the Venetian soldiers.

The Milanese and the Mantovans managed to penetrate with a fleet through a canal dug between Panego and the river in April 1439, and in a few days Piccinino and Gonzaga took Legnago, Porto, Lonigo, Castelbaldo, Brendola, Montecchio Maggiore, Arzignano, Montorso, Valdagno, and finally Soave.

Control of these important centres in the Verona and Vicenza plains allowed them to attack Verona with their full forces and sack it. The Venetian defeat was very serious, but it appears certain that the responsibility lay mainly with Andrea Donà, podestà of Padua and Venetian provveditore, who decided to divide the troops across the various fronts, ultimately weakening them. He thought he could save the bulk of the Venetian army by ordering Gattamelata to withdraw from Verona and set up camp between Este and Montagnana. Gattamelata left the Lebrecht Palace where he was staying and abandoned Verona. He did not agree with this decision but complied. A few months later, he suffered a stroke and retired for good. He died in Padua in 1443

The arrival of the Venetian fleet in Garda was of little use, because the Milanese, after their initial astonishment, were able to react. The struggle continued for several years, but eventually Brescia returned to Venetian rule and remained so until 1797.